Beautiful bog nymphs

You’re out on a bog and large, brown butterfly drifts past on the summer breeze. Odds are it’s a large heath, but the chances of seeing one of these butterflies is getting slimmer. Globally, the large heath butterfly is under threat, largely due to habitat loss1. They are listed as vulnerable in Europe by the IUCN UK Red List with the main threat listed as land drainage, mostly due to agricultural improvements2.

Large heath butterflies (Coenonympha tullia) are specialists of bogs and wet heathland. They are found across northern and central Europe, but only sporadically due to their reliance on suitable habitat. Globally, they are found in the Holoarctic region, across northern and central Europe, northern Asia and North America. There are an incredible 31 described sub-species across their range, with three in the UK: davus in lowland England, scotica in northern Scotland, and polydama elsewhere.

From left to right: large heath subspecies davus (credit Iain Leach), scotica (credit Peter Eeles) and polydama (credit Iain Leach).

In the UK, large heaths are mostly found in northern Britain, Northern Ireland and a few sites in Wales and central England. They breed in lowland raised bog, upland blanket bog and wet moorlands which are home to their caterpillars’ food plant, hare’s-tail cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum). According to Butterfly Conservation, caterpillars are also occasionally found on common cottongrass (E. angustifolium) and jointed rush (Juncus articulatus). Their breeding sites are usually below 500m in areas with the caterpillars’ food plants, as well as Sphagnum moss and cross-leaved heath - the main source of nectar for adult butterflies3.

Hare's tail cottongrass, Eriophorum vaginatum. Credit Lorne Gill, SNH.

Identification

The large heath is a medium-sized brown butterfly with underwing spots, similar to the small heath butterfly, though the latter is generally found in drier areas. The large heath always sits with its wings closed and has a distinctive cream band below its forewing eyespot, and a line of spots towards the edge of its hindwing. However, the three subspecies in the UK have different sizes of underwing spots. Davus is heavily spotted, scotica is virtually spotless and polydama is in-between4. Adults usually fly between June and August, and can even fly on dull days in temperatures as low as 14°C.

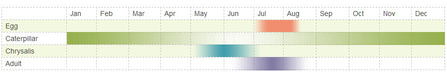

The large heath’s eggs are round and pale yellow, and are laid singly often on dead stems. They take around two weeks to hatch. The caterpillars, which are green with darker green and white/yellowish stripes running the length of the body, feed until September. They hibernate within the vegetation, emerging in March and then pupating in April/May. Lifecycle chart courtesy of Butterfly Conservation.

Large heath caterpillar. Credit Peter Eeles.

Lifecycle chart courtesy of Butterfly Conservation

Local extinctions

Research by Butterfly Conservation has shown that the large heath’s UK range decreased by a staggering 58% between 1976 and 20144. The large heath has declined across England and Wales, though it is still widespread in parts of Scotland and Ireland. Locally, the large heath may not seem like it is declining – they live in large, distinct colonies with up to 15,000 individuals. However, they rarely fly very far once they have emerged from their cocoons, meaning that populations become isolated from each other and more vulnerable. Alongside this, the area of lowland raised bog in the UK has declined by around 94% due to drainage for agriculture, afforestation and peat extraction5. These factors have led to local extinctions of large heath butterflies, particularly in England and Wales, and the butterfly is listed as Endangered in the UK.

Butterfly Conservation are working with partners across Northern Ireland to contribute to peatland conservation efforts, not least by supporting species monitoring through the UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme to better understand its status. While Northern Ireland is considered a stronghold, Butterfly Conservation need to investigate and update the status for the region6.

In Scotland, Butterfly Conservation’s ‘Bog Squad’ project has been working on lowland raised bogs since 2014. A group of dedicated volunteers work on several bogs carrying out small-scale restoration through scrub clearance and ditch blocking. This in turn improves the habitat condition of peatlands for large heath and other bog biodiversity. Through volunteer-led large heath surveys and monitoring across peatlands in Scotland, Butterfly Conservation is starting to build a clearer picture of the butterfly’s status and the condition of its habitat, which will contribute towards long-term trends for the species7.

Bog Squad at Kingshill damming. Credit Polly Phillpot.

Recovering populations

It has been found in Cors Fochno in Wales that where successful peatland restoration work has taken place, large heath butterfly populations have remained stable. It is important to continue to monitor large heath butterflies to understand their population dynamics, habitat preferences (particularly in areas of peatland restoration) and to understand the impacts of climate change8.

There is potential that peatland rewetting as part of restoration efforts could negatively affect existing large heath caterpillar populations as they can be affected by rising water levels. In the winter, caterpillars often hibernate at the bottom of cottongrass plants, and submergence has been found to have a marked impact on their long-term survival9. This impact should be considered in stronghold areas for the large heath, but restoration to wetter and more hydrologically stable peatlands across the UK will benefit the species in the long term.

Overall, research suggests that healthy populations of large heath butterflies can be used as an indicator of good-quality lowland raised bogs due to their ecological requirements for wetter sites with a reliance on bog plant species for their lifecycle. Therefore, overall, any peatland restoration work for large heaths should also have positive impacts on other peatland species1.

Large heath pupae in a release enclosure. Credit Andrew Hankinson.

As well as peatland restoration, there has been success with direct reintroductions of large heath butterflies. They are unlikely to naturally recolonise areas where they have become locally extinct because they only disperse short distances, and there are often large distances between suitable habitat locations. The IUCN Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations state the need for a clear understanding of a species’ biotic and abiotic habitat requirements, evidence based decision-making and ongoing monitoring and management adjustment in the light of new evidence10. Research into these aspects means that species reintroductions are more likely to be successful. In the case of the large heath, extensive research has been undertaken and used to inform site selection for reintroductions1.

Large heath release enclosure. Credit The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside.

Bringing back the Manchester argus: a reintroduction case study

Locally known as the Manchester argus, the large heath butterfly went locally extinct in the Great Manchester Wetlands over 100 years ago due to drainage and peat exploitation. However, thanks to the huge amounts of work that have gone into restoring lowland peatlands by The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside (LWT), and the Great Manchester Wetlands Species Reintroduction Project, large heath butterflies can now be seen in the area once more.

Using adult donor populations from Winmarleigh Moss, eggs were collected and the resulting caterpillars reared in bespoke enclosures at Chester Zoo. Mature pupae were transported from the zoo and acclimatised in mesh tents at Heysham Moss and Astley Moss, where peatland restoration work has ensured the habitat is once again suitable for the species.

Collecting a large heath donor population at Winmarleigh Moss. Credit The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside.

Since 2014, hundreds of adult butterflies have been released and surveys at Astley Moss in 2023 recorded over 90 large heath flights. The reintroductions have been deemed a success and the population will now be left to increase naturally11. Monitoring of the butterfly population and the peatland habitat will continue to ensure the continued health and growth of the population. The hope is that, eventually, the large heath butterfly will return to other areas of the Greater Manchester peatlands, along with other lost species being given a second chance thanks to peatland restoration.

Visit our biodiversity pages to read our other species showcases and find out more about the importance of peatland restoration in bringing back biodiversity.

References

- Osborne A, Longden M, Bourke D, Coulthard E. Bringing back the Manchester Argus Coenonympha tullia ssp. davus (Fabricius, 1777): Quantifying the habitat resource requirements to inform the successful reintroduction of a specialist peatland butterfly. Ecological Solutions and Evidence. 2022;3(2).

- IUCN. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023-1. www.iucnredlist.org [Accessed 6th June 2024].

- Butterfly Conservation. Large Heath Priority Species Factsheet. https://butterfly-conservation.org/sites/default/files/large-heath-psf… [Accessed 2024 Jun 06].

- Butterfly Conservation. Large Heath. Large Heath | Butterfly Conservation (butterfly-conservation.org) [Accessed 6th June 2024].

- BRIG (Ant Maddock ed.). UK Biodiversity Action Plan: Priority Habitat Descriptions - Lowland Raised Bog. 2008.

- Cremin R. Senior Conservation Officer at Butterfly Conservation. Personal communication. 12th June 2024.

- Phillpot P. Peatland Restoration Project Officer at Butterfly Conservation. Personal communication. 15th July 2024.

- Lyons J. Large Heath Butterfly monitoring within Cors Fochno SAC, 1986 to 2022. Natural Resources Wales. 2023.

- Joy J, Pullin AS. The effects of flooding on the survival and behaviour of overwintering large heath butterfly Coenonympha tullia larvae. Biological Conservation. 1997;82(1):61–66.

- IUCN. Guidelines for reintroductions and other conservation translocations. 2013.

- The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire, Manchester and North Merseyside. Rare Manchester argus butterflies flourishing after reintroduction. Rare Manchester argus butterflies flourishing after reintroduction | The Wildlife Trust for Lancashire Manchester and North Merseyside (lancswt.org.uk) [Accessed 13th June 2024].